Written by: Cynthia Verling, PHSS Intern

Imagine you are walking on a sunny day in the lovely city of Cape Coral and stumble across a burrow! You wonder, who made this carefully crafted burrow their home? Is it a mole? Is it a gopher? It’s a burrowing owl! With bodies reaching a maximal length of 9.8 inches and a wingspan of 21.6 inches, these one of a kind avians are one of the smallest owls in the State of Florida and are classified as State Threatened by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC)., These ground-dwelling owls create burrows and nests underground, as hinted at within their scientific name, Athene cunicularia – cunicularia meaning to mine or burrow in Latin. Unlike the usual image of owls peering down from trees in dense forests, burrowing owls live in vast open habitats, such as grasslands. Their burrows can stretch for lengths ranging from 6 to 10 feet, consisting of intricate tunnels weaving about 3 feet below the surface containing several bends and paths at the end of which a chamber can be found that harbors their nest., Some owls will use existing burrows or even pipes to build their burrows. The entrances to these humble abodes consist of mounds of dirt, grass, human trash articles, and are also covered intentionally by the owl with animal dung to attract insects which they can then eat. Their burrows not only serve to store away food in plentiful amounts during the period of incubation and brooding, but also provide an environment in which temperatures are better regulated and further aid in preventing the owls from dehydration during very hot days. Although, with increasing human developments and urbanization, habitat loss is an imminent and ongoing threat to these owls. In response, these owls begin to build burrows in urban environments, such as golf courses or even airports. Characteristic traits of adult burrowing owls include their dazzling yellow eyes, spindly long legs that allow them to get a better outlook from the ground-level, short tails, brown dorsal feathers with white spots and white ventral feathers with brown bar-shaped patches, distinct white eyebrows and throats, and characteristic round heads without the familiar ear tufts commonly seen in woodland owls., Nestlings on the other hand have cream-colored downy feathers that have less distinct speckles. Their diet consists mostly of insects but can also include other small birds, fish, rodents, and particularly in Florida, reptiles, such as snakes, frogs, and lizards, as, after all, raptors are carnivores.

The burrowing owl is arguably a perfect embodiment of the idiom “rare bird,” as it has so many unique attributes that set it apart from other birds in the family Strigidae. In addition to their peculiar small size and absent ear tufts, these owls are diurnal rather than nocturnal during the breeding season, thus showing activity during the daytime., Known to be very animated and sprightly, it is not uncommon to see these owls bobbing and bouncing up and down, while nestlings will even playfully leap at one another and prey, accruing at the same time important behavioral skills to prepare them for hunting later in life. Interestingly, nestlings also are known to imitate the rattling of a rattlesnake from within the protection of their burrows as a defense mechanism to ward off unwanted visitors, such as predators and humans., As a consequence of being the only species that perch on the ground, burrowing owls behave differently than one would expect; for example, if bothered or hunting they can be seen pushing themselves flat against the ground or running, respectively, as opposed to flying like owls usually do. Even more fascinating is that unlike other raptors, where the female is visibly larger than the male, which is termed “reverse sexual dimorphism,” female and male burrowing owls are the same size, with the latter being only a mere 3% larger – a size difference imperceptible to the naked human eye at first glance. Furthermore, male and female Burrowing Owls bear the same coloration, which is interesting as sexual dimorphism dictates that female and male conspecifics have traits that differ between them, and in many birds, this usually results in males exhibiting a visibly larger size or significantly more extravagant plumage coloration or ornamentation– traits that serve in courtship or competition for mates. Burrowing Owls pair for life, and unusual for an owl, are not solitary, but rather prefer to live in small colonies. This can be explained by the principle of group living, believed to have evolved independently in many different species. Group living confers advantages such as greater protection against predators, group defense, increased feeding efficiency, sharing of behaviors and communicating information, increased rate of reproduction due to access to potential partners, shelter, division of labor, and social thermoregulation. Burrowing Owls exhibit such social behaviors as the male and female even take turns in incubating the eggs, foraging, and caring for the offspring. Therefore, smaller species are often found living together in groups. Lastly, due to the significant amount of time they spend underground where there is less oxygenated air, they have an adaptation that confers them an increased tolerance for carbon dioxide.

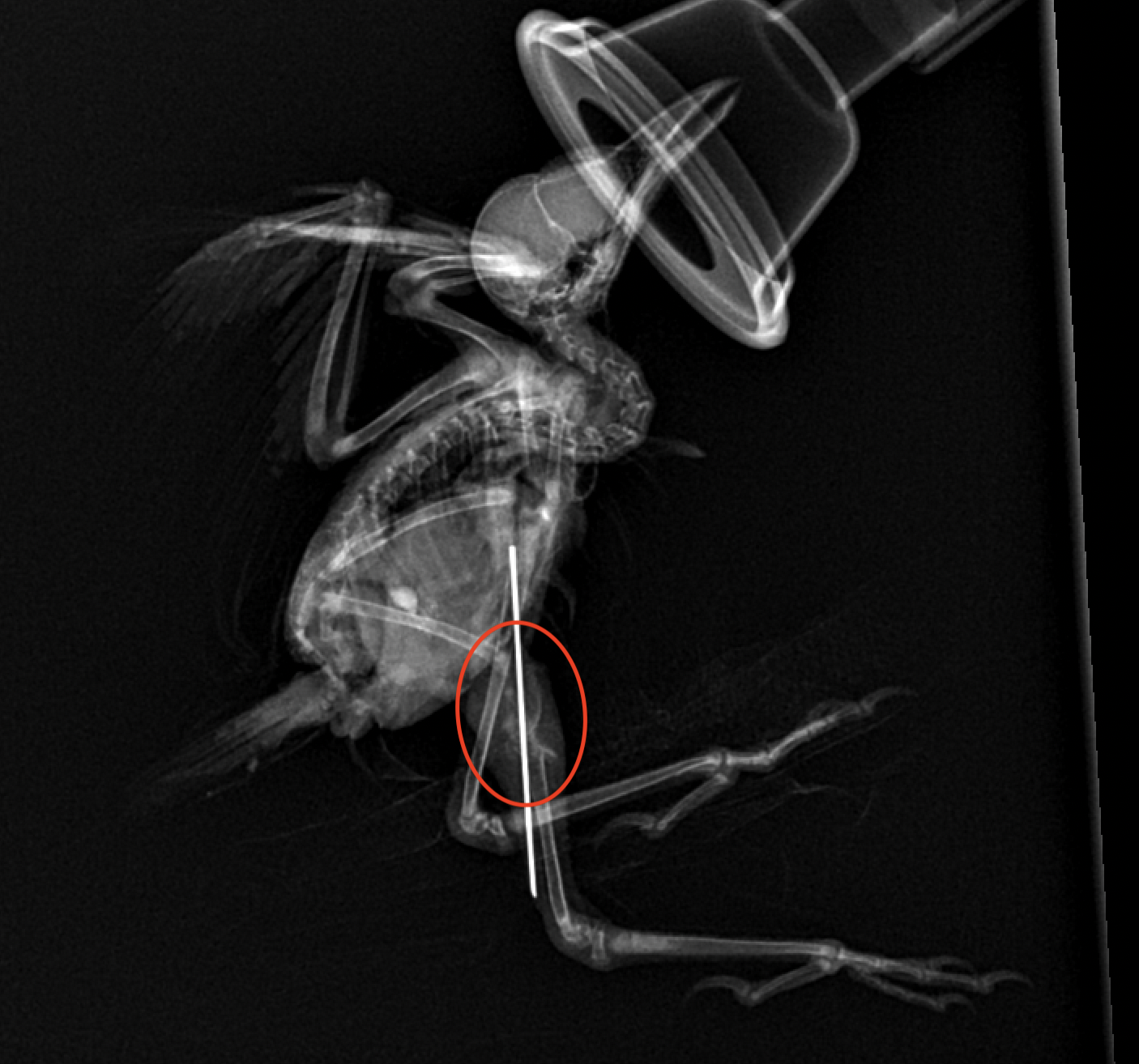

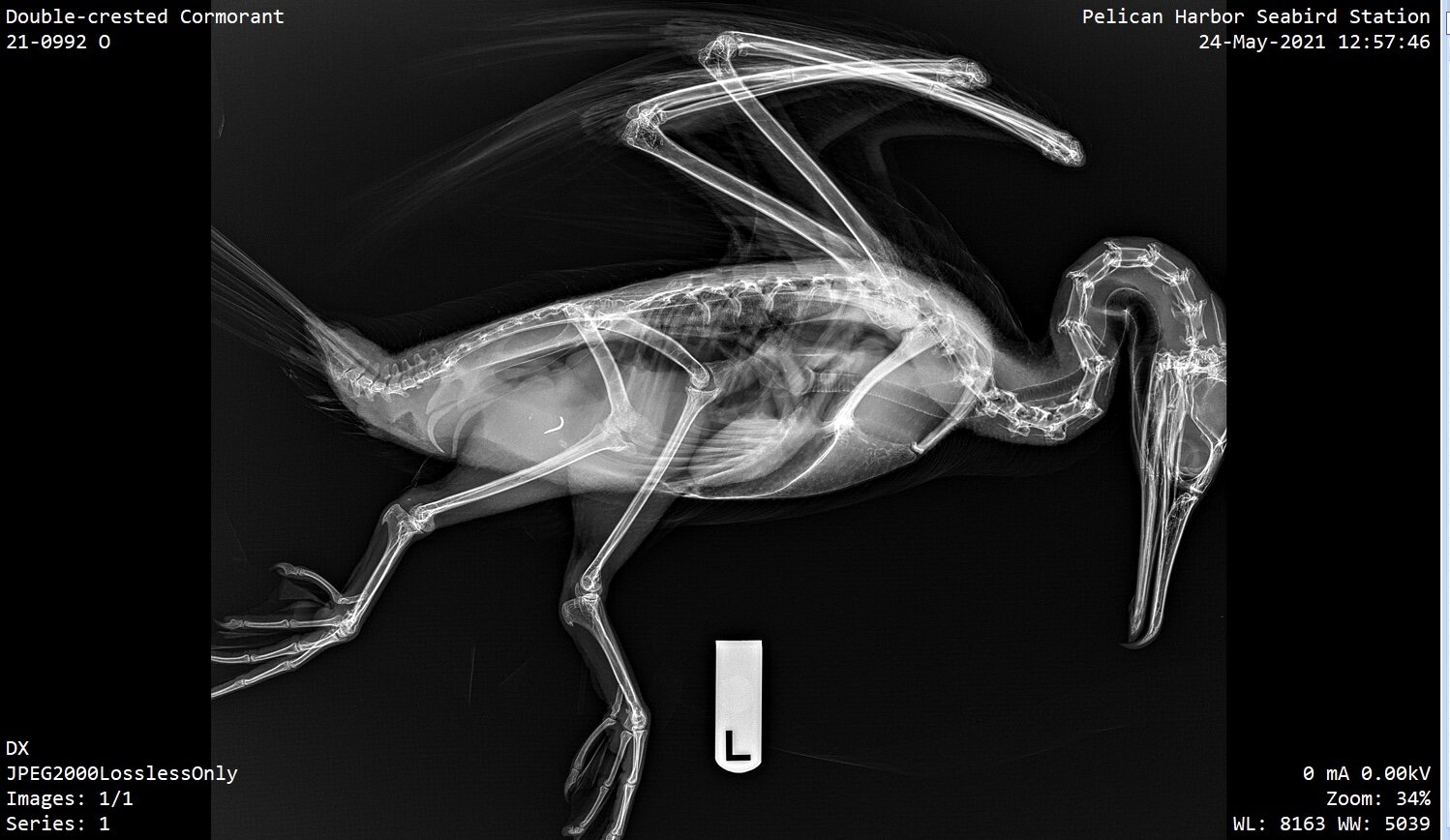

These incredible avians are, however, under threat of habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, as well as climate change, and rodenticide poisoning, which all have long-lasting impacts on entire ecosystems. Burrowing owls fall victim to secondary rodenticide toxicosis called “bioaccumulation” when they consume rodents that have consumed rodenticide., Second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs), e.g., brodifacoum, are slow-acting anticoagulants, which result in the rodents not dying instantly. This leads to poisoned rodents slowly becoming weak, but because they are not instantly killed, they roam about, becoming more easily caught by predators such as Burrowing Owls. Bioaccumulation, however, causes for the period the rodent is alive to allow for a buildup of toxins to a much greater lethal dose. As the owl consumes the rodent, the toxin moves through the food web from rodents (secondary consumers) to burrowing owls (tertiary consumers), running the risk of accumulating even greater lethal amounts of poison over time at a rate greater than it can be broken down, this time in the burrowing owl. Brodifacoum is according to one source, the most widely used rat poison in the United States, and has a very long half-life in animals. A study conducted from 2006 to 2010 at Tufts Wildlife Clinic at Tufts University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine reported that from 161 birds, 86% had anticoagulant rodenticide residues in their liver tissues, of which 99% had brodifacoum in their liver tissues. Moreover, only 9 of these birds that tested positive exhibited clinical symptoms, demonstrating that many affected may not show visible signs of poisoning, which is critical given the concern of bioaccumulation at an ecological level. SGARs function by inhibiting the enzyme vitamin K reductase, which under normal conditions allows for the reactivation of vitamin K – a fat-soluble vitamin that plays a vital role in the coagulation cascade by producing coagulation factors I, II, VII, IX, and X in the liver and synthesizing Protein C, Protein S, and Protein Z that serve to prevent thrombosis., During the coagulation cascade, the factors produced by vitamin K are crucial to allowing the downstream activation of prothrombin to form thrombin, the latter of which ultimately stimulates the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, which traps platelets to form a spongy mass that hardens into a blood clot and prevents one from bleeding out. Additionally, the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab explains that animals commonly have stores of clotting factors that delay the full effect of poisoning for 3-5 days following ingestion and the hemorrhaging onset. While coagulation panels (a blood test) exist for diagnosing anticoagulant rodenticide toxicosis in domestic animals, there are currently no existing blood tests for birds to screen for rodenticide toxicosis. Burrowing owls that get a lethal dose through consuming an affected rodent face an inhumane slow death from internal or external bleeding that causes them to weaken, which may cause them to obtain injuries in the meantime, until either the hemorrhaging or other life-threatening injuries sustained while weakened eventually kill them. If rodenticide toxicosis is evident, vitamin K can be administered to act as an antidote and help restore the blood coagulation cascade to normalcy. Additionally, stomach flushing, inducing vomiting, and administering activated charcoal are all treatments that may be used to prevent additional absorption of toxin by the body.

Raptors such as Burrowing Owls play a critical ecological role both in the wild and in urban areas. Rodenticide toxicosis in these incredible avians is not just an issue to be left to conservationists and wildlife rescue and rehabilitators, but is a public issue that must be addressed at the source to prevent further systemic damage throughout food webs, as maintaining a sustainable and biodiverse ecosystem is a necessary goal for conserving, protecting, and restoring healthy and vibrant wildlife and their habitats and by extension and directly in relation also human health, as we are all connected and a part of the planet’s ecosystem.

Sources:

Conway, Courtney J. “Burrowing Owls: Happy Urbanite or Disgruntled Tenant?” In Urban Raptors: Ecology and Conservation of Birds of Prey in Cities, edited by Boal C.W., and Dykstra C.R., Washington, DC: Island Press, 2018.

Cornell University. “Burrowing Owl: Identification.” The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Cornell University. “Raptors and Rat Poison.” The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Cornell University. “Rodenticide Toxicity.” Cornell Wildlife Health Lab

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “Burrowing Owl.”

Libre Texts. “Role of Vitamin K.” Last modified August 13, 2020.

National Audubon Society. “Guide to North American Birds: Burrowing Owl.”

National Geographic. “Biomagnification and Bioaccumulation.”

National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. “Sea Wonder: Burrowing Owl.”

Owl Research Institute. “Burrowing Owl: Athene cunicularia.”

Vallejo, David. “Animal’s social behavior: Group living.” Zoo Portraits. July 17, 2018.